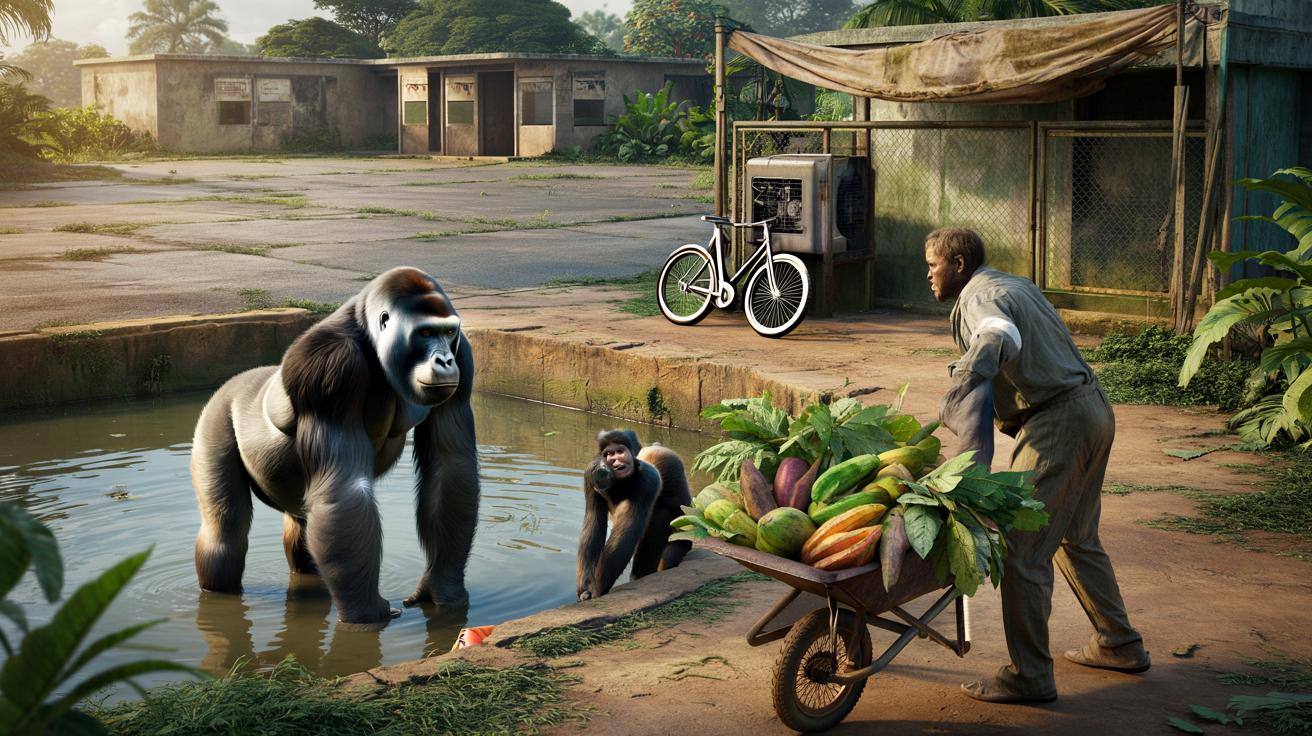

Three years after the gates clicked shut, a troop of gorillas still wakes to the rattle of a wheelbarrow and the smell of overripe fruit. The park is closed, the ticket booths blanked out, the souvenir shop stripped. Yet the primates remain, marooned in an attraction that no longer exists on paper but very much persists in reality.

A former keeper leans his bike against the rusting fence, flips back a tarpaulin and lifts a crate of plantains as though the ritual might keep time from slipping. Across the moat, a silverback rises, watching with the weary authority you see in long-serving station guards.

Beyond the empty car park, a generator coughs into life. The power line failed months ago. That’s when the water pumps started sulking.

And then the gate clanged shut.

Gorillas in a park that no longer opens

When a park closes, you assume the animals go somewhere. In this case, the animals stayed, because moving them is not like boxing up the tills. A skeletal team kept showing up, paid late or not at all, clinging to a duty that outlived the business. The signage faded, the Instagram stopped, but the feeding chart remained stubbornly neat.

The troop learned the rhythm of an empty crowd. Kibu, a 23-year-old silverback, still taps the same log at 9am, expecting carrots. He gets fewer carrots now. On Tuesdays, if the wholesaler is kind, there’s papaya. On bad weeks, it’s sweet potatoes and leaves and a little maize porridge. The maths is unforgiving: a group like this chews through roughly 60 kilos of produce a day. At local market rates, call it £700 a week when prices surge.

People ask why they’re not “just” moved. The short version is permits, quarantine, and relationships you can’t bubble wrap. Great apes don’t pack well. You need export and import papers under CITES, a receiving sanctuary with space, vets who can manage heavy sedation without stressing a tight-knit group, and transport that won’t break them. In parallel, you need lawyers to unwind a corporate shell that has no money but still holds the animals on its books. That’s the **legal limbo**.

What helps now, without causing more harm

Start with consistent support rather than showy bursts. A vetted fund that covers fresh produce, hay, browse, and generator fuel steadies the week-to-week. Ask for line-item budgets. If an NGO can present last month’s feed invoices, you’re in the right place. Small recurring gifts beat erratic windfalls, because gorillas don’t skip dinner when social media cools off.

Think about noise. Viral outrage rarely moves paperwork but it can spook a sensitive troop. Better to phone the competent authority quietly, follow up in writing, and keep notes. Where it makes sense, write to your MP asking the UK to back an emergency translocation, especially if a British charity is involved. Let’s be honest: nobody does that every single day. Doing it once, properly, counts.

Be wary of “voluntourism” that adds more humans to a stressed environment. Short-stay helpers need training, carry disease risk, and burn staff time the apes could use. If you want to be practical, join remote shifts: grant-writing, translation, shipping logistics, cold emails to airlines for freight waivers.

“You can feel the moment the truck arrives with decent greens,” says Maria, a senior keeper who never left. “They eat slower. The little ones stop glancing at the fence.”

- Give to a group with CITES experience and audited accounts

- Ask for monthly spend on feed, fuel, vet meds

- Support a realistic relocation plan, not a fantasy release

- Amplify verified updates, not rumours

- Offer skills before you offer flights

The long wait, and what it reveals about us

There’s a strange etiquette to places that hang around after people leave. The grass grows into the pathways, the paint peels, and routines hold the whole thing together like old string. This is where the gorillas live now: not in a scandal, not in a story, but in a daily loop of food, cleaning, dozes, stares, and quiet arguments over good branches.

We’ve all had that moment when a responsibility outlives the job title. For the keepers, this isn’t theoretical. Their patience is the bridge between what was promised and what can still be done. It isn’t romantic. It’s maintenance: order enough bananas, check the waterline, track the weights, keep the peace in a social group that reads your mood the second you come around the corner.

*There’s a danger that the spectacle of abandonment becomes the whole point.* It isn’t. The point is whether a collection of contracts, stamps, and budgets can align quickly enough to spare a thinking animal needless months of waiting. One outcome is a permanent sanctuary with trees that don’t end at a concrete edge. Another is a managed future on-site, secured and funded, the gates shut not from neglect but on purpose, with care. The future is still editable.

To understand why the gorillas are “still there”, you have to accept a dull truth about complicated rescues: paperwork moves at the speed of politics, while hunger moves at the speed of hunger. That gap is where citizens matter. A letter may nudge a desk. A small donation may become five bags of greens. A patient public helps experts keep their heads down and hands steady. That’s the **quiet emergency**.

Some readers will ask where this park is and why it isn’t named in bright lights. The sober answer is that naming a site before plans are locked can invite pressure or opportunists. What can be named is the to-do list: fuel, food, permits, crates, vet cover, cargo space, receiving capacity. None of it is mythic. All of it is doable. And yes, in the background, a silverback is still watching for that familiar wheelbarrow.

| Point clé | Détail | Intérêt pour le lecteur |

|---|---|---|

| Why the gorillas remain | CITES permits, quarantine, social cohesion, and a company in wind-down | Cuts through noise to the real blockers you can help unlock |

| What it costs each week | Roughly 60 kg of produce daily; spikes push costs near £700/week | Turns concern into a concrete sense of urgency and scale |

| How to help well | Back audited groups, steady giving, quiet advocacy, skills not selfies | Offers a path that actually improves ape welfare, not just clicks |

FAQ :

- Where is this park?On the edge of a tropical city in Central Africa. The location is withheld while legal and relocation plans firm up to avoid harmful pressure.

- Why not release the gorillas into the wild?Most captive-born or long-captive gorillas lack the survival skills and social context for a safe release. Ethical options are accredited sanctuaries or a secured, improved home-range on-site.

- Is this even legal?Yes and no. The animals are protected, but the entity that held them collapsed. Authorities and NGOs are working through ownership, duty-of-care, and transfer permissions. That’s the **three years** in one line.

- Are the gorillas safe right now?They are being fed and monitored by experienced staff. Risks remain: power failures, supply gaps, storms, and the stress of uncertainty. Stability depends on steady support.

- How do I verify a charity before I give?Look for audited accounts, named staff, recent field photos with context, specific budgets, and partnerships with known ape sanctuaries. Email them a simple question and see if they answer clearly.